by Christophe Ponsard (CETIC) and Ward Desmet (Computer Museum NAM-IP)

Museums play a key cultural role through the immersive experience they provide. Their accessibility for all was threatened by the COVID-19 lockdowns. In response, many museums, including our Computer Museum, have accelerated their digital transformation for improved online or hybrid experiences, with benefits for accessibility but also possibly new barriers to address.

Museums preserve cultural artifacts and make them accessible to present and future generations, through an immersive access to public. They rely on exhibitions and specific events such as conferences and workshops, which can target a specific audience. Museums remain essentially "brick-and-mortar" spaces and as such, they must meet legal physical accessibility requirements with specific standards, regulations, assessments and tools for supporting this process. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered many digital initiatives in museums [L1], including in our Computer Museum located in Belgium [L2].

All museums have to manage multiple interactions with a varied public from kids to seniors and mobility-impaired people. It is also a workplace for curators, experts, animators, etc. Such audiences can be characterised through archetypal descriptions embodying their user stories, called personas [1]. The following personas cover important accessibility goals:

- Alice, an animator with young kids, would like to regularly work remotely in full collaboration with her colleagues to keep a good balance in her work/private life.

- David, a deaf visitor, would like to register online, benefit from subtitling in videos and possibly specific signed language tours.

- Frank, a foreign visitor, would like to enjoy the exhibition in his native language or English.

- Walter, a wheelchair-using visitor, would like to prepare his visit through a virtual tour and consult information in an accessible way for an optimal experience.

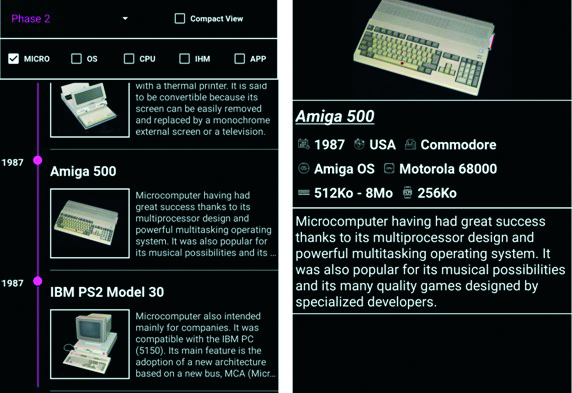

Digital technologies can provide support for those user stories but the whole personas have to be kept in mind in order to identify emerging accessibility threats. For example, web forms enable remote access for David but must be accessible according to web standards like WCAG. This also applies to the nice virtual tour of the IN2P3 Computer Museum [L3] depicted in Figure 1 – while it may help Walter, it may also be more difficult to reach good digital accessibility given the complex multimedia navigation interface. Many museums also propose a mobile application either on a specific terminal or to install. Figure 2 depicts an example developed in our museum. It will help Frank, given the multilingual support, and David, through the subtitling features, but at the same time may prove difficult to use for Walter, given the need to swipe on a timeline while moving his wheelchair. Finally, the ease of information access for Alice from home may vary depending on the mix of online collaborative tools, off-line files, email and possibly available VPN access.

From the user experience, it is interesting to analyse how advanced technologies such as the development of virtual tours or mobile applications really support the museum scenography. Different approaches exist from the basic transposition of the physical experience, e.g., video of a guided tour or paper guide made available online. The virtual museum is a more complex case. It might involve unusual controls that need to be validated for accessibility and regarding the learning curve, e.g., through a tutorial or possibly through a virtual guide (avatar). The pure transposition of the physical world into a digital one is interesting for hybrid experiences (preparation before arrival) but it might also overload the user with uninteresting information/actions (corridor pictures, the need to point in the right direction). It is interesting to consider a more conceptual level stated with goals and narratives [2]. This led us to develop our mobile application depicted in Figure 2, which can relate various artifacts, people, organisations and technologies through a timeline mechanism, enabling the support of a physical visit but also the exploration of other relationships beyond what is “hard-coded” in the physical exhibition [3]. Another interesting and possibly complementary approach is gamification; it allows the user (not only kids) to engage more deeply with the content.

Figure 1: Virtual tour of the IN2P3 Computer Museum.

Figure 2: Mobile app of the NAM-IP Computer museum.

To summarise, new online channels can help to reach a larger and multilingual audience. Consequently, emerging threats relate to online accessibility or the interconnection between the physical and digital worlds. Some web accessibility problems are well known but others are less common and require more attention, e.g., virtual navigation or mobile apps. The use of personas, possibly reflecting user preferences and abilities or disabilities, is efficient in discovering such barriers and mitigating them. We are currently reconsidering them from a more global perspective, integrating a more immersive on-site and online user experience.

Links:

[L1] https://pro.europeana.eu/post/mapping-museum-digital-initiatives-during-covid-19

[L2] https://www.nam-ip.be

[L3] https://musee.cc.in2p3.fr

References:

[1] A. Cooper: “The inmates are running the asylum”, Macmillan Publishing Company, 1999.

[2] M. Mason: “The elements of visitor experience in post-digital museum design”, Design Principles and Practices, 2020.

[3] C. Ponsard, A. Masson and W. Desmet: “Historical Knowledge Modelling and Analysis through Ontologies and Timeline Extraction Operators: Application to Computing Heritage”, MODELSWARD 2022.

Please contact:

Christophe Ponsard, CETIC, Belgium

+32 472 56 90 99