by Evangelos Markatos (FORTH and University of Crete), Mary Aiken, Julia Davidson (University of East London), Alexey Kirichenko (F-Secure Corporation) and David Wright (Trilateral Research)

Over the past few years, we have seen cybercrime rising to become a trillion-dollar business world-wide. Although the cost of cybercrime was close to $5.5 trillion in 2020 [1], it is now estimated to double by 2025 [2]. To put this number in perspective, a cost of $10.5 trillion a year is $28 billion per day, or $20 million a minute, or close to $330,000 a second. At such staggering rates, it is imperative to understand the drivers of cybercrime and how they can be mitigated.

Our study on the technical drivers of cybercrime, within the EU-funded CC-DRIVER [L1] project, suggests that our digital society and attendant technical developments offer immense opportunities for cybercriminals. Take, for example, the proliferation of IoT devices that surround us: smart watches, smart phones, smart light bulbs, smart coffee makers, smart vehicles, smart homes, smart cities and, in fact, “smart everything”. All of these smart entities have computing and communicating capabilities, which present a wide array of opportunities and attack vectors for cybercriminals. These smart devices are entry points to a private internal communication network in a home. If any of these smart devices are unprotected, cybercriminals can compromise the device and, from that one, they will be able to enter the home network. They may be able to probe the front door, scan the household PC, surveil the local traffic, deploy man-in-the-middle attacks, and create an account to permanently establish their presence – an insider threat in the home. These smart devices are “digital steppingstones” to a well-mounted attack. Notably, our affinity and increasing dependence on all things digital continue to increase the number of steppingstones.

As an example of technical drivers of cybercrime, we can consider the ever-evolving phenomenon of cryptocurrencies. Over the past few years, people have started to use cryptocurrencies not only to transfer money, but also as an alternative form of investment. Unfortunately, the anonymity, or indeed the pseudonymity, provided by the main crypto coins creates an ideal vehicle for cybercriminals to use crypto currencies for their financial transactions. In many aspects, cryptocurrencies are as good as, or sometimes even better than, cash. They are anonymous, they can be sent all over the world instantly, they do not involve any physical transfer of bills, and they leave few traces.

To protect their legal right to privacy online, legitimate network users use various mechanisms, such as anonymising networks and/or services that can provide some form of privacy. Such mechanisms include incognito browsers, cookie blockers, Virtual Private Networks (VPNs), and anonymising networks (such as Tor – 'the onion router' and entry point to the dark web). Although such systems are helpful for protecting the privacy of legitimate users, they can also be abused by cybercriminals to operate anonymously. This anonymity, especially as provided by Tor and similar networks, enables cybercriminals to hide their tracks and their illegal activities and, in doing so, evade detection by law enforcement authorities (LEAs).

In addition to the above and other technical drivers of cybercrime, our research has revealed a significant factor that has contributed to the current proliferation of cybercrime. Findings illustrate that the business model of cybercrime has moved from the “one-man-show”, ad hoc type activity to organised “cybercrime-as-a-service”, serious business operations. In the old days of cybercrime, one person, or a small number of closely collaborating people, were responsible for the entire cybercrime operation: from hacking into accounts all the way to shipping stolen goods. Things are different today. As cybercrime has become increasingly organised and tech-enabled, cybercriminals have started to specialise and become experts in niche areas. This has now evolved to a point where one cybercriminal might be an expert at hacking, another at recruiting, yet another at money-muling, and so forth. In this new operational scenario, everybody has become an expert at something, but few perpetrators are expert at everything. Cybercrime-as-a-service has, therefore, evolved as a means to help cybercriminals with different expertise collaborate in their criminal enterprise, combining and syndicating skillsets to create a whole operation that is greater than the sum of its parts. As soon as the cybercrime-as-a-service model started to gain traction and deliver results, increasing numbers of cybercriminals rushed to offer their services. Undoubtedly, this cybercrime model was facilitated by "offender convergence settings" in cyberspace, that is, dark nets in the dark web, for example: “hacking-as-a-service”, offered to hack into accounts; “bulletproof-hosting-as-a-service”, offered to host illegal operations; and “DDoS-attacks-as-a-service”, offered to attack remote computers.

All of these technical drivers and the novel “as-a-service” business model make it evident that cybercrime is a highly adaptable, agile and growing business with new threat actors and criminal groups continuously entering the field. Understanding the models and the drivers is of the utmost importance for successfully countering cybercrime.

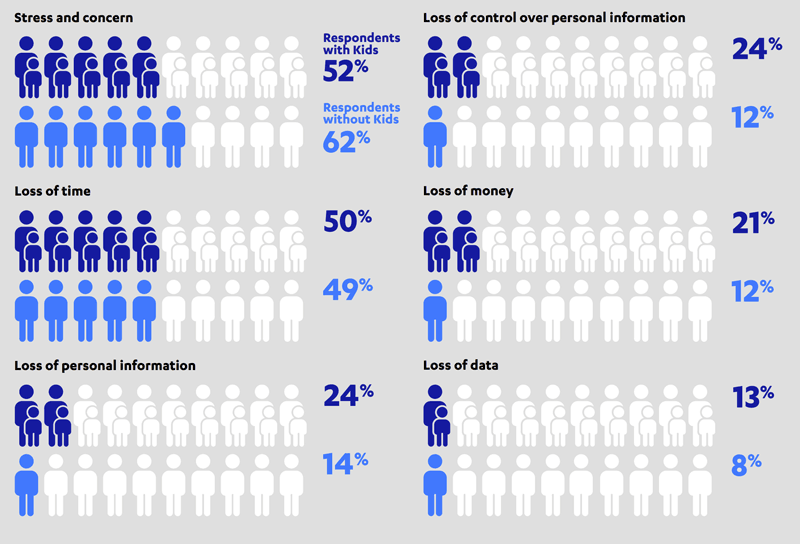

Figure 1: Effects of Cybercrime experienced by victims (source: F-Secure [L2]).

CC-DRIVER has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No 883543. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors only and are in no way intended to reflect those of the European Commission.

Links:

[L1] https://www.ccdriver-h2020.com/

[L2] https://www.f-secure.com/content/dam/press/en/media-library/reports/F-Securen%20The%20Walking%20Breached%20-raportti%209.2.2021.pdf

References:

[1] European Commission and High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy: “The EU’s Cybersecurity Strategy for the Digital Decade”, Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council, Brussels, 16 Dec 2020, p.3.

[2] S Morgan: “Cybercrime to Cost the World $10.5 Trillion Annually By 2025”, Cybercrime Magazine, 13 Nov 2020. https://cybersecurityventures.com/hackerpocalypse-cybercrime-report-2016/

Please contact:

Evangelos Markatos, FORTH-ICS