Attila Bekkvik Szentirmai (University of South-Eastern Norway)

We built an inclusive augmented reality guitar to make music-making accessible to almost anyone. But our tests revealed a paradox: can too much accessibility undermine an instrument’s authenticity?

Inclusive Music Making

Playing a traditional instrument is rewarding but also demanding. Mastery often requires years of practice, physical dexterity, and significant financial investment. These barriers exclude people with physical, sensory, or cognitive impairments, and anyone without the resources, time, or early training to participate.

Accessible Digital Musical Instruments address these barriers by applying universal design principles to make interfaces usable by as many people as possible [1]. For a recent review, see Frid [2]. While these tools expand participation, they also raise questions about the value we place on effort, skill, and mastery.

GuitAR: A Low-Cost, Inclusive Augmented Reality Guitar

We developed GuitAR to explore new ways of making music accessible. It combines a lightweight physical guitar body with a digital augmented reality (AR) interface overlay (see Figure 1). The physical body is a laser-crafted wooden piece without acoustic strings or moving parts, sized to suit most adult ergonomic needs. The guitar uses a high-contrast, sticker-bombed surface for reliable computer vision and object tracking.

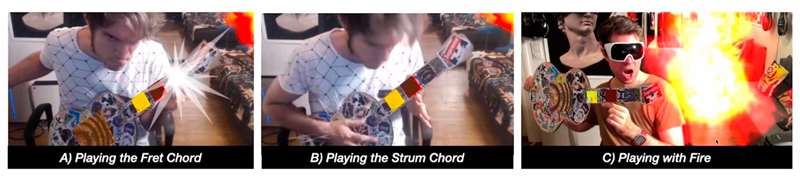

Figure 1: GuitAR in use: (A) playing a fret chord; (B) strumming; (C) themed video effect (flames), as a user enjoys the AR experience.

The application is compatible with low-cost Android smartphones, keeping costs and entry barriers low. Computer vision detects the guitar marker, tracks user input, and overlays digital frets and a strummer in a third-person view (see Figure 1A–B). Players create music by interacting with digital chords through physical touch or air gestures. In addition to sound, real-time interaction effects and themed video effects, such as flames (see Figure 1C), play to make music creation more engaging. Design choices were informed by universal design heuristics for mobile augmented reality [3].

User Delight Meets Skepticism: The Paradox of Too Much Accessibility

We pilot-tested GuitAR with a small, diverse group that ranged from complete beginners to an experienced guitarist. Most had never used AR before.

All participants quickly grasped the concept, strummed chords, and experimented freely. They enjoyed the instant ‘perfect’ power chords, the visual effects, and found the interaction playful and intuitive. The experienced guitarist, however, was unconvinced: ‘It feels more like a toy than an instrument,’ he remarked when GuitAR was introduced as an instrument. He explained that, for him, playing GuitAR was too easy, suggesting that an instrument’s legitimacy depends not only on producing music but also on the effort and skill required to master it. Two other participants directly mentioned Guitar Hero, a video game with a guitar-shaped controller, as a similar ‘game,’ which reinforced the perception that our design felt more like a game than an instrument. Similar critiques have met many innovative instruments. Electronic keyboards, drum machines, and DJ controllers were once dismissed as ‘toys,’ yet became accepted once their creative potential was shown. Authenticity, in this sense, is not fixed but shaped by culture over time.

However, user feedback revealed a clear tension. After years of advancing AR accessibility and universal design to transform the technology from a barrier into a facilitator across application domains ranging from utility to education, we found that excessive simplicity in music creation can erode an instrument's perceived value, especially in areas where mastery confers prestige. This represents a critical insight that future inclusive design practice must further address.

A Question for Accessible Digital Futures

GuitAR prompts a broader question for responsible innovation. When we make technology more accessible, which social and cultural values do we change along the way? The same paradox appears in other creative fields, such as AI-generated art, text, code, and video editing. Tools that democratize self-expression can also devalue results in the eyes of some, simply because the production process is so easy.

Inclusion is essential, but if learning, overcoming difficulty, and demonstrating skill give an activity its meaning or identity, removing those elements may also diminish its perceived value. This is not an argument against accessibility. It is an invitation to rethink inclusive design so that we deliver solutions that are easy to begin yet offer depth, authenticity, and challenge for those who want to go further. We suggest that inclusive design should not only remove barriers, but also find ways to preserve the cultural value of mastery, ensuring that accessibility and authenticity coexist.

Links:

[L1] GuitAR (short video demonstration): https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14927801

[L2] GuitAR Hero - The World’s first lasercrafted AR Guitar: https://xrresearch.pubpub.org/pub/guitar

References:

[1] M. F. Story, “Maximizing usability: The principles of universal design,” Assistive Technology, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 4–12, 1998.

[2] E. Frid, “Accessible digital musical instruments, a review,” Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, vol. 3, no. 3, p. 57, 2019.

[3] A. B. Szentirmai and P. Murano, “New universal design heuristics for mobile augmented reality applications,” in Proc. International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, pp. 404–418, 2023.

Please contact:

Attila Bekkvik Szentirmai

University of South-Eastern Norway, Department of Business and IT, Norway