by Emmanouela Kokolaki and Paraskevi Fragopoulou (FORTH-ICS)

In Greece, SafeLine—the national hotline for reporting illegal online content and a core service of the Greek Safer Internet Center under the auspices of the Foundation for Research and Technology–Hellas (FORTH), is the first officially recognized Trusted Flagger under the Digital Services Act (DSA). Among its key activities is monitoring emerging challenges brought about by new regulatory developments. At present, a matter of particular concern to the Greek Hotline regarding children's access to online services is age estimation techniques. Do these practices truly serve the best interests of children, or do they risk reinforcing surveillance and bias at the expense of fostering genuine inclusion?

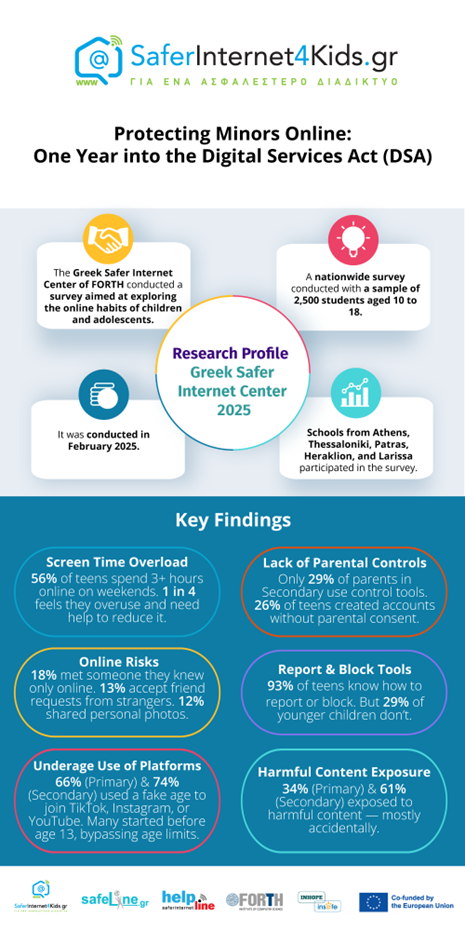

A key research focus for SafeLine [L1] is children's online habits in relation to the DSA’s provisions (Figure 1), with particular emphasis on age assurance and the widespread circumvention of age limits on very large online platforms (VLOPs). Within this context, age estimation has emerged as a key method to enable effective age assurance mechanisms. Age estimation refers to methods used to determine a user’s likely age or age range [1]. The relevant processes may involve automated analysis of behavioural or environmental data, monitoring user interactions with devices or other users, utilizing metrics from motion analysis, testing the users’ cognitive capacities and employing biometric classifiers. According to the Commission’s “Guidelines on the protection of minors under the DSA” [L2], the implementation of age assurance measures is a key approach to ensuring minors' privacy, safety, and security on online platforms by restricting access to age-inappropriate content and by mitigating risks such as minors’ exposure to grooming behavior. Along with self-declaration and age verification, age estimation is one of the most commonly employed age assurance measures. Before applying age-based access restrictions, providers must assess the necessity and proportionality of such measures, and determine whether alternative, less intrusive measures can offer an equal level of protection.

Figure 1: Online research findings.

Age estimation techniques are considered by the Commission to be an appropriate and proportionate measure to protect minors’ privacy, safety, and security when either (i) platform terms set a minimum age below 18 due to identified risks to minors, or (ii) medium-level risks identified through a risk assessment cannot be mitigated by less restrictive measures. For age estimation to be considered an appropriate and proportionate measure, however, it is essential that it be conducted either by an independent third party or through independently audited systems that ensure security and adherence to data protection standards. Notably, the Guidelines expressly classify as inadequate an age estimation system with a ±2-year error margin, when a medium-risk platform restricts access to users under 13. Such error rates can both admit users under 13 and exclude eligible users.

In its Statement 1/2025 on Age Assurance, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) underscores the importance of applying General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) principles when processing personal data in the context of age assurance, stating that a provider should prevent the age assurance process from leading to unnecessary data protection risks such as those resulting from profiling or tracking natural persons [2]. This raises the question of whether practices involving automated behavioral analysis fall within the scope of AI-driven profiling, and consequently, whether minors may exercise the right to opt out. Accordingly the EDPB strongly emphasizes that unnecessary processing and storage of personal data should be avoided when biometric data are processed, due to the seriousness of risks associated with age assurance systems. The EDPB further advances this position in its comments on the Commission’s Draft Guidelines [L3], stating that, due to the high incidence of false positives and negatives, as well as the significant interference with users’ fundamental right to data protection, the use of algorithmic age estimation should generally be discouraged.

Building on these concerns, the question arises under the EU Artificial Intelligence Act: could facial age estimation systems be classified as high-risk? This classification would apply if such systems are “intended to be used for biometric categorization, according to sensitive or protected attributes or characteristics based on the inference of those attributes or characteristics” [L4]. While it is obvious that facial age estimation assigns people to age categories, its ability to infer additional sensitive attributes is less certain. Should facial age estimation systems be classified as high-risk, strict compliance with the relevant obligations including the establishment of risk management system, is required. In general, it appears that the EDPB’s emphasis on data minimization aligns with the AI Act’s requirements for risk management measures, as limiting data inherently serves as an effective risk mitigation mechanism, thereby underscoring a convergence between the two approaches.

In terms of real-world applications, Yoti, a UK-based provider [L5], has developed facial age estimation technology, which is also used by Instagram as one of the verification methods when users attempt to change their date of birth from under 18 to over 18. Roblox, on the other hand, employs a facial age estimation method to assign users to the correct age category [L6]. In this context, another consideration for platforms operating across multiple jurisdictions is the fragmented regulatory framework governing age assurance. Across OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) jurisdictions, age limits may differ depending on the applicable legal regime (such as privacy, or consumer protection [L7]). At the same time, protection related to children’s access to online pornography varies significantly: while all OECD countries prohibit access in general, just over half explicitly address online content, and only a handful provide detailed age assurance requirements. Privacy and data protection frameworks provide the most consistent age limits. However, implementation remains fragmented, as age thresholds for parental consent differ across countries.

Concerns have also been raised regarding potential biases of facial age estimation technologies. Evidence suggests [3] that the technical reliability of such models is often undermined by the lack of globally representative training data. However, the use of web-scraped personal data to meet this need raises legal implications under the GDPR [L8]. Additionally, humans are inherently biased age estimators and AI-based age estimation tools may further amplify these biases [3]. Moreover, data leakage has been acknowledged as a significant risk, and accordingly, France’s CNIL recommends performing facial analysis locally on the user’s device to mitigate this threat [L9].

Overall, while age assurance is becoming a focal point of digital policy, its implementation remains highly challenging due to the complexity of complying with diverse legal frameworks and the risks associated with AI-based age estimation techniques. These risks spanning surveillance, unnecessary processing of biometric data, algorithmic bias, and digital exclusion highlight the pressing need for age assurance systems that are not only effective but also firmly grounded in fundamental rights and ethical design principles.

Links:

[L1] https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/commission-publishes-guidelines-protection-minors

[L2] https://www.edpb.europa.eu/system/files/2025-06/edpb_comments_europeancommission_article_28_dsa_en.pdf

[L3] https://developers.yoti.com/age-verification/age-estimation

[L4] https://en.help.roblox.com/hc/en-us/articles/39143693116052-Understanding-Age-Checks-on-Roblox#:~:text=Facial%20age%20estimation,-We%20estimate%20your&text=Your%20estimated%20age%20helps%20place,will%20be%20removed%20from%20Roblox.

[L5] https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2025/06/the-legal-and-policy-landscape-of-age-assurance-online-for-child-safety-and-well-being_cdf49a15/4a1878aa-en.pdf

[L6] https://www.edpb.europa.eu/system/files/2025-06/spe-training-on-ai-and-data-protection-technical_en.pdf

[L7] https://www.greens-efa.eu/en/article/document/trustworthy-age-assurance

References:

[1] OECD, “The legal and policy landscape of age assurance online for child safety and well-being”, OECD Technical Paper, June 2025 https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2025/06/the-legal-and-policy-landscape-of-age-assurance-online-for-child-safety-and-well-being_cdf49a15/4a1878aa-en.pdf

[2] EDPB, “Statement 1/2025 on Age Assurance, point 2.3 and 2.4, Feb. 2025. https://www.edpb.europa.eu/system/files/2025-04/edpb_statement_20250211ageassurance_v1-2_en.pdf

[3] Ofcom, “Statement: Age Assurance and Children’s Access”,2025 https://www.ofcom.org.uk/siteassets/resources/documents/consultations/category-1-10-weeks/statement-age-assurance-and-childrens-access/statement-age-assurance-and-childrens-access.pdf?v=397036

Please contact:

Emmanouela Kokolaki, FORTH-ICS, Greece

Paraskevi Fragopoulou, FORTH-ICS, Greece