by Anna Szlávi (Johannes Kepler University), Minh Dan Nguyen (Norwegian University of Science and Technology)

The scarcity of women in computing – broadly STEM –is a persistent challenge. A number of interventions have been dedicated to tackle the key challenges related to the gender gap; the Erasmus+ “Women STEM UP” project being one of these efforts. In this article, we provide details about tools and resources developed for setting up a mentorship program for a better gender inclusion in the field.

The Women STEM Up project [L1], a consortium of Linköping University (Sweden), the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (Norway), Thessaly University (Greece), Stimmuli for Social Change (Greece), and the Digital Leadership Institute (Belgium), was aimed at making STEM education more gender-inclusive and more attractive to women students. Lasting from February 2024 until April 2025, Work Package 3 of this project was to create freely downloadable resources to launch mentoring programs specifically for female STEM university students throughout Europe.

Mentoring has been found to be a key success factor for marginalized groups within computing. Specifically for women, it has been shown to function as a facilitator for entering and staying in STEM [1]. To increase gender balance in the field, it is crucial to dedicate efforts to recruit more women, as well as to retain those already in computing education or careers, for which mentoring can be an effective tool [2].

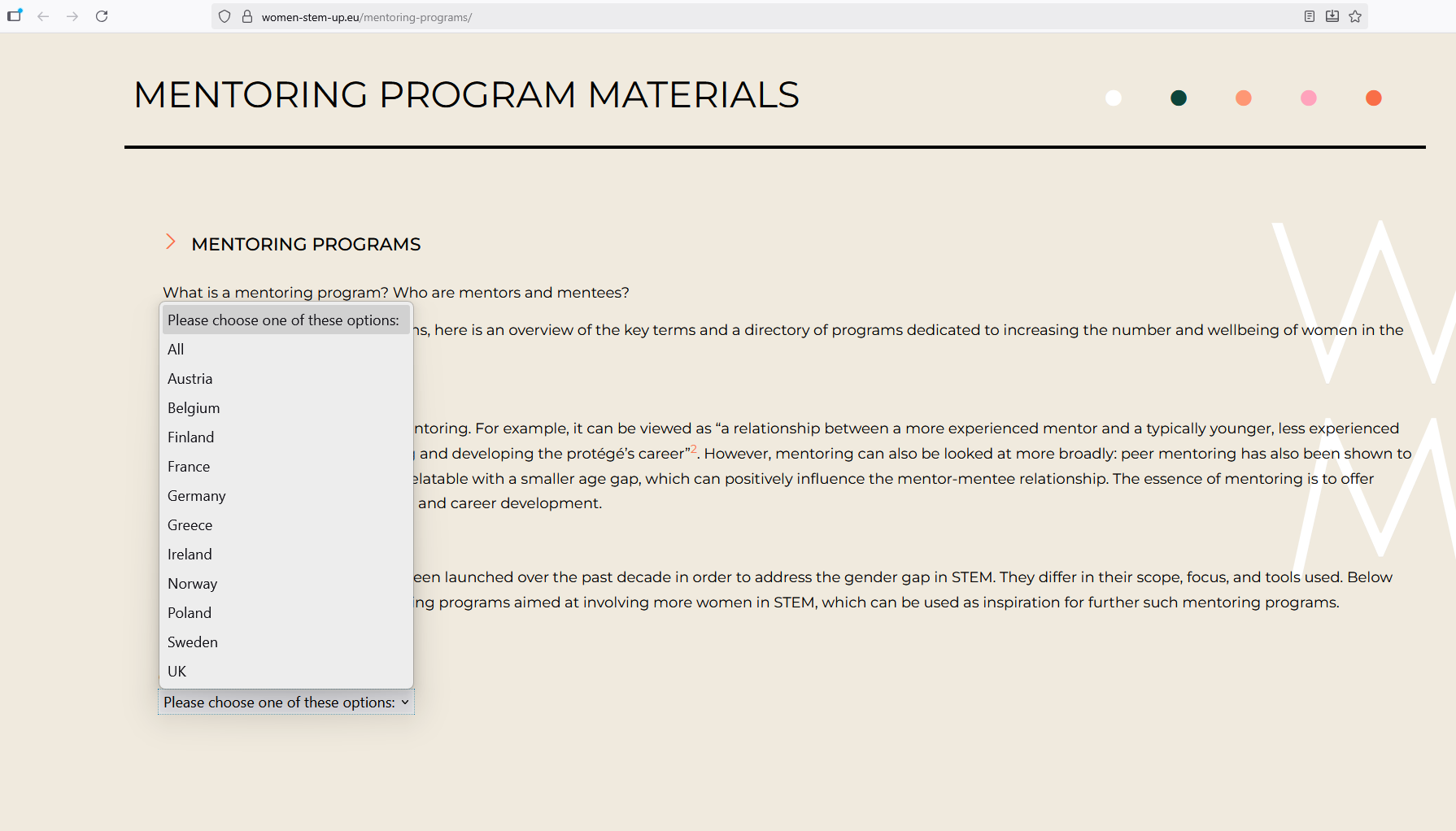

It is, however, necessary to have the know-how about how to set up and operate a mentoring program. One of the goals of this project, therefore, was to create tools which can be used by any institution interested in increasing gender balance through mentoring. In addition to offering an overview of the terminology associated with mentoring, the project website offers a list of past and existing mentoring programs [L2], with the aim of providing best practices and inspiring further interventions. The directory, as displayed in Figure 1, is searchable by country so that stakeholders can more easily find relevant programs.

Figure 1: Searchable directory of mentorship programs on the website.

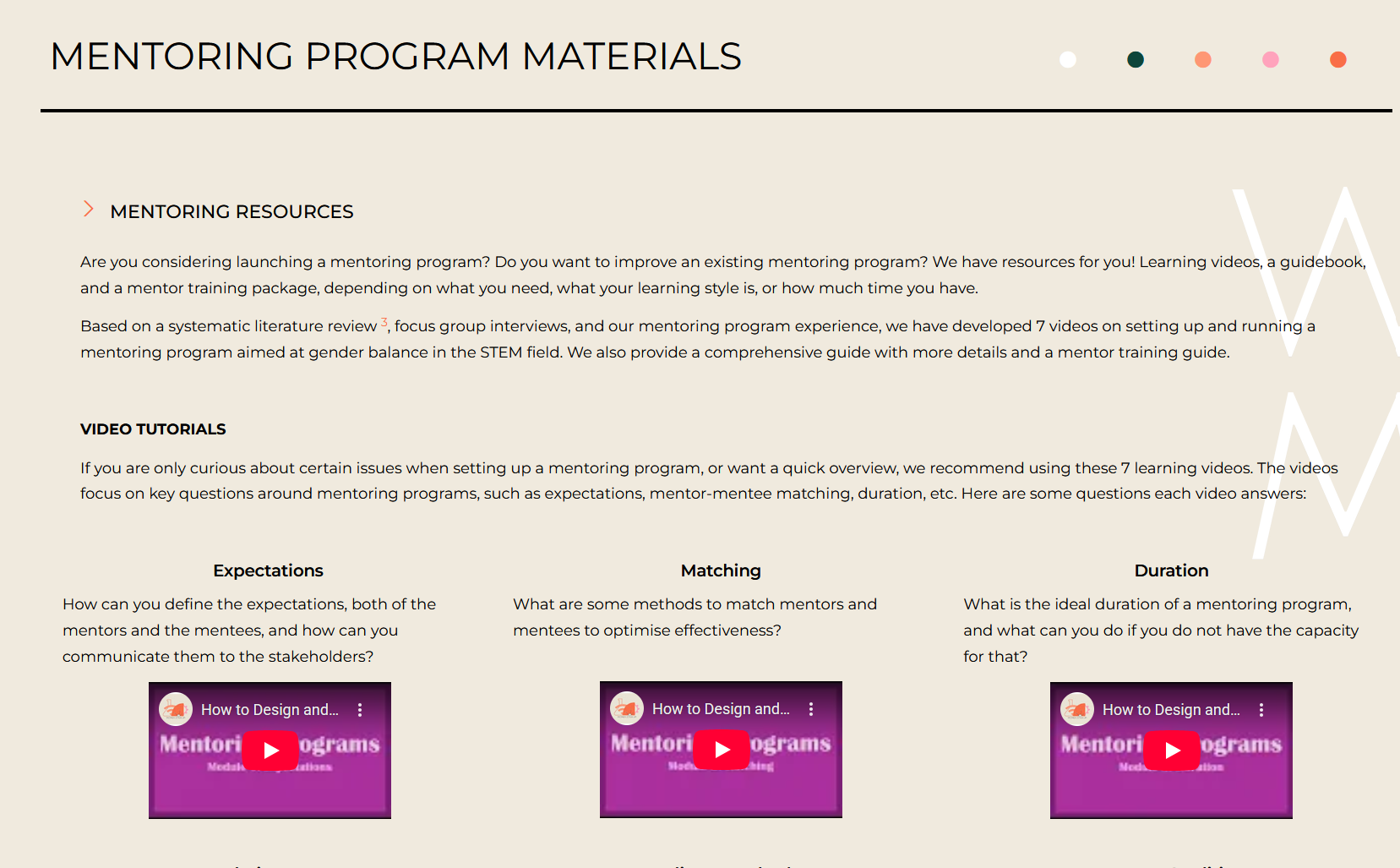

The project also provides mentoring resources for institutions who are interested in launching a mentoring program. On the one hand, we offer a quicker learning path through a series of videos, available on the website [L3] and on YouTube [L4]. As seen in Figure 2, there are seven learning videos dedicated to different aspects of what to consider when setting up a mentoring program, such as defining a goal, managing expectations, matching mentors and mentees, and comparing e-mentoring vs face to face mentoring.

Figure 2: Mentoring resources on the website.

In addition to the quicker learning path provided by videos, we have also created a more detailed approach to guiding institutions to set up a mentoring program for women in STEM in the form of a guidebook [L5] and a mentor training packet [L6].

The above resources were introduced to and assessed by staff and faculty of the partner universities in the autumn of 2024. After the hybrid training events, we made the resources freely available and downloadable from the website. In addition to the original – English – version, we added the French, Greek, Norwegian, and Swedish translations as options (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: The downloadable guide and mentor training packet on the website.

To further test them, the resources were also shared with the mentors who participated in the project’s own mentorship program, between November 2024 and March 2025, dedicated to support women studying at partner institutions. After the mentorship program ended, the mentors were asked to provide feedback on the resources.

Some mentors highlighted the value of the content and information provided in the training packets:

“The training packet was indeed helpful; It was insightful and highlighted important information around boundaries and confidentiality.”

“The mentor training packet provided useful guidance on mentorship objectives, helping to clarify the roles of both mentor and mentee and ensuring a well-defined approach. It also deepened my understanding of the mentor's role and how to approach it effectively to best support the mentee’s professional growth.”

Other mentors emphasized the training packet’s importance for first-time mentors in particular:

“The mentor training packet was good! There were very good tips, especially for first timers.”

“The mentor package was great! Honestly, I was a bit insecure about the mentorship because it was my first time mentoring someone outside my specific area of expertise, but it helped me take the risk.”

However, some mentors pointed out some aspects of the training packet which could be improved:

“Your mentorship pack was very extensive, with valuable information, however, it was information overload [...]. It could be simplified and made shorter to really highlight the core messages and valuable content you have created.”

“I felt the need for more interactive elements and case studies: the guide is providing solid theoretical insights, but incorporating real-life mentoring cases, scenarios on how to manage various situations, self-assessment checklists could enhance the program.”

As mentioned by the mentors themselves, the mentor training packet was a valuable tool, which could provide the mentors both with insight and information. The additional knowledge helped the mentors prepare and understand their role better, which in return enhanced the mentees’ experience of the mentoring process. However, it is crucial to take note of the flaws and continue to improve the training packet to ensure that the mentors are equipped with the necessary skills for such a mentoring program.

After implementing the project’s own mentoring program for women in STEM, we ran surveys to see its success. We can conclude from the feedback of the mentees that even a short mentoring program can positively affect their self-efficacy, thus, improve their chances of retention [3]. We, therefore, recommend setting up – even short or experimental – mentoring programs to support women in the field, for which the tools developed and provided by the Women STEM Up project can be a good start.

Links:

[L1] https://women-stem-up.eu/

[L2] https://women-stem-up.eu/mentoring-programs/

[L3] https://women-stem-up.eu/mentoring-resources/

[L4] https://tinyurl.com/2rzm2y73

[L5] https://tinyurl.com/3hnz7vt7

[L6] https://tinyurl.com/r2xktbye

References:

[1] A. Szlávi, et al., “Mentoring as a Tool for Better Gender Diversity in Informatics,” in Actions for Gender Balance in Informatics Across Europe, B. Penzenstadler, K. Boudaoud, S. Caner Yildirim, and A. Di Marco, Eds. Cham: Springer Nature, 2025. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-78432-3_5

[2 B. Trinkenreich, et al., “An Empirical Investigation on the Challenges Faced by Women in the Software Industry: A Case Study,” in Proc. Int. Conf. Software Engineering in Society (ICSE-SEIS’22), Pittsburgh, PA, USA, May 21–29, 2022. New York, NY, USA: ACM, 2022, pp. 1–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1145/3510458.3513018

[3] M. D. Nguyen, “Evaluating the impact of mentorship programs on students’ self-efficacy,” M.S. thesis, Norwegian Univ. of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, Norway, 2025.

Please contact:

Anna Szlávi, JKU, Austria