by Arianna Rossi (SnT, University of Luxembourg)

People know that once they publish something online, such content becomes "publicly available" and can be downloaded and re-used by others, for example, researchers and data scientists. The reality is far more complicated. And for us, finding a way to comply with data protection obligations and to respect the tenets of research ethics became an exploration of a largely uncharted territory.

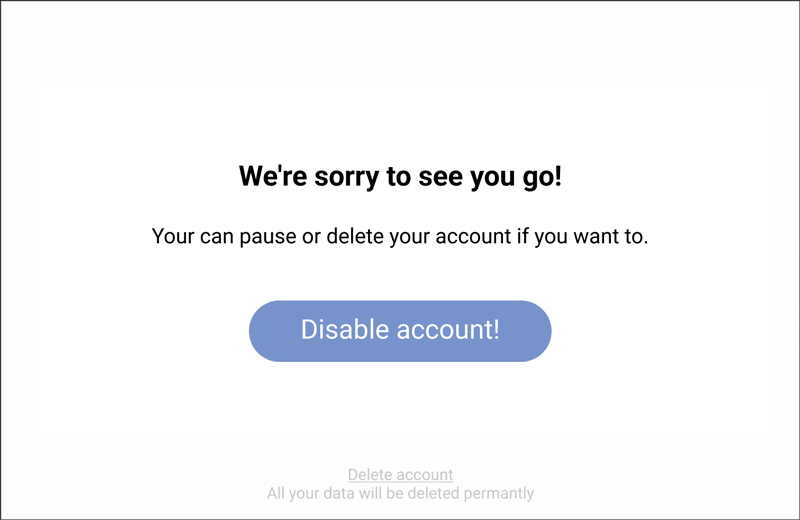

Within an interdisciplinary project (Dark Patterns Online "DECEPTICON" [L1]) carried out at the SnT, University of Luxembourg, together with the Human-Computer Interaction group and the Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology, we are gathering examples about the many manipulative designs that populate online services (i.e., dark patterns, see Figure 1) and are publicly condemned on Twitter and Reddit. Our aim is to build a labelled dataset of such pervasive practices by using crowdsourced knowledge and possibly develop supervised machine learning models to flag dark patterns at scale.

Initially, we were convinced that we only needed to address a few data protection concerns, which seemed totally feasible. However, we found out that there is a plethora of legal obligations to comply with and additional research ethics principles to be considered. Finding creative answers to such issues was a long, tiresome, albeit formative experience that we briefly share in these pages, with the conviction that it can be of help to other academic and industrial researchers who collect and analyse internet data.

First, we need to ask: what may count as personal information on social media? The answer is: Potentially, almost everything. Not only the username and pictures can reveal a users' identity, but also metadata like the timestamp, the location and URLs contained in tweets and online posts can trace back to specific people. Moreover, a simple search online of a tweet or part of it can easily lead to its authors and all the associated information. It also means that merely removing usernames from a dataset does not equal anonymising data, as data scientists often argue in their papers. Consequently, we fall within the realm of the General Data Protection Regulation and thus we should observe many obligations about the transparent, lawful and fair processing of personal data.

To enhance data confidentiality, for example, many security measures must be implemented, like encrypting the dataset and only using encrypted channels to transfer it to a private Git repository, which must be subject to strong authorisation and access-control measures. We also pseudonymised the data, i.e., we masked or generalised data like personal names, locations and timestamps, and implemented a re-identification function that can re-establish the original data at will, for example to retrieve the authors of social media posts and allow them to opt out from our study. We are now examining more advanced and secure techniques for pseudonymisation.

We also experimented innovative ways to be transparent: we published a privacy policy that followed best practices of legal design, for instance a conversational tone that clarifies what are the responsibilities of the researchers as opposed to the rights of the social media users, and we emphasised the main information to allow skim reading. Since such a privacy notice is tucked away on our project's website, the possibility that a Twitter user stumbles upon it is extremely weak, so we set an automated tweet that once a month alerts about our invisible data collection and gives practical instructions on how to opt out of it.

Apart from these and other data protection measures, we also had to embed research ethics into our activities. Contrary to what many scientists believe, research on internet data counts as research on human subjects, and must therefore offer the same level of safeguards. However, data scraping mostly happens without the knowledge of the research participants who thus don't have the option to freely decide whether to take part in the study or not. Since we extract content that has been disclosed in a certain environment, sometimes within a closed community, we need to foresee the possible consequences of extrapolating, reusing and disclosing such information in a different context. Given that seeking the informed consent of thousands of people may be impossible, we tried to be very transparent about our activities and gave the possibility to opt out of the study. This is why we pseudonymised the data, so that we could exclude certain parts of them on demand. Additional details, including other issues like how to treat minors' data, how to address cyber risks and how to attend to data quality in such specific settings are described in [2].

Reflecting on our time-consuming experience of producing innovative multidisciplinary solutions, we asked: given the time pressure of the academic world and that unethical and illegal behaviour is only rarely sanctioned, what kind of incentives could encourage internet data researchers to go through the same pain as us? Training, even when based on immersive, entertaining experiences, is necessary, but not sufficient: the intention–behaviour gap remains unsolved and when procedures are too complex, human beings find workarounds to what they perceive as obstacles.

Thus, the second order of solutions should make compliance and ethical decision-making less burdensome. Practical guidance drafted in laymen terms, as well as best practices and toolkits tailored to certain technologies should be created and proactively brought to the attention of researchers. Moreover, we need usable off-the-shelf solutions that simplify and expedite academic compliance tasks. We are now working on an open-source Python package for social media data pseudonymisation [3].

We start to see the light at the end of this ethics-legal maze and hope that our Ariadne's thread will guide other legality-attentive researchers [L2] out of it.

Links:

[L1] https://irisc-lab.uni.lu/deceptive-patterns-online-decepticon-2021-24/

[L2] https://www.legalityattentivedatascientists.eu/

References:

[1] K. Bongard-Blanchy, et al., “I am Definitely Manipulated, Even When I am Aware of it. It’s Ridiculous! - Dark Patterns from the End-User Perspective”, in Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2021 (pp. 763-776). 2021.

[2] A. Rossi, A. Kumari, G. Lenzini, “Unwinding a Legal and Ethical Ariadne’s Thread out of the Twitter’s Scraping Maze”, in Privacy Symposium 2022—Data Protection Law International Convergence and Compliance with Innovative Technologies (DPLICIT), S. Ziegler, A. Quesada Rodriguez and S. Schiffner, Springer Nature (in press).

[3] A. Rossi, et al., “Challenges of protecting confidentiality in social media data and their ethical import”, in 2022 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW), pp. 554-561, IEEE, 2022.

Please contact:

Arianna Rossi, SnT, University of Luxembourg, Luxembourg