by Maria Dagioglou (NCSR ‘Demokritos’, Greece) and Vangelis Karkaletsis (NCSR ‘Demokritos’, Greece)

For this teaser we were asked to describe what is the article about, who is doing what and why. Fittingly enough, this is literally what we discuss in this article: in human-robot collaboration, who is doing what and why?

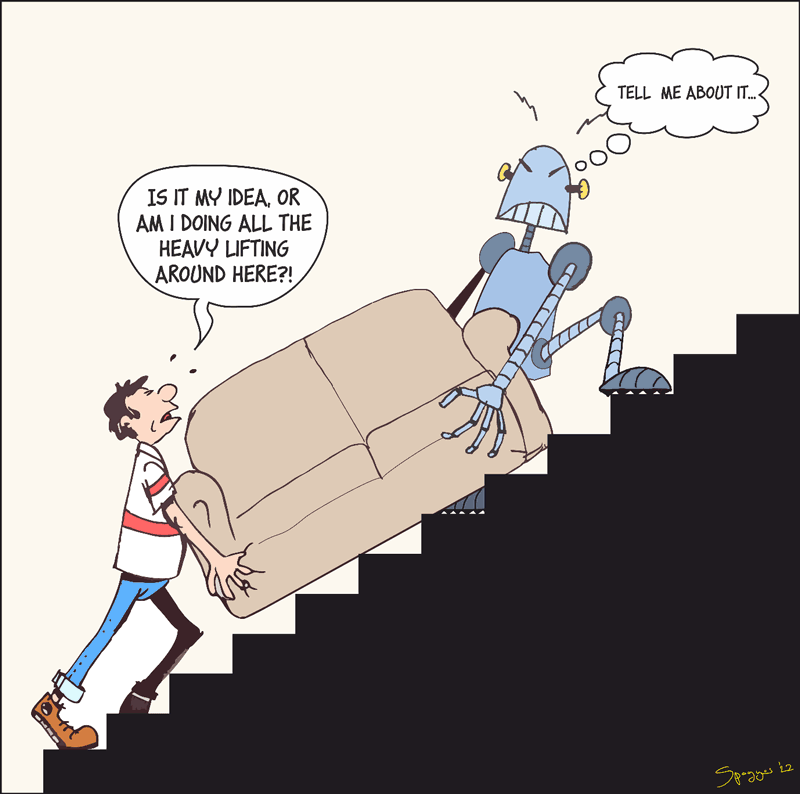

Figure 1: During collaboration it might be difficult to differentiate between self- and other-generated actions. Understanding our partner is crucial for fluent and transparent performance. Drawing by Stefanos Poirazoglou for the purposes of this article (CC BY 4.0).

From carrying a heavy object to supporting a rehabilitation exercise, humans coordinate their bodies and minds to move together and achieve mutually agreed goals. During collaborative tasks, each partner needs to: know what the other perceives (or not), be able to predict his/her actions based on action observation and the requirements of the shared task, decide when and how to act for supporting team performance and efficiency [1]. In addition to all these, the spatio-temporal proximity of actions during collaboration affects the sense of self- and joint-agency. Who bears the authorship of a joint action’s outcome? The experience of acting as a team, the nature of the task (competitive or complementary) and the fairness of resource distribution are only some of the factors that shape the perceptual distinctiveness of each partner’s actions.

Now, what about human-robot collaboration (HRC)? What if a human were to collaborate with a robot to carry a sofa up the stairs (Figure 1)? In the context of this article, HRC is considered as the case of a human and a collaborative robot (cobot) that work in close proximity (within the intimate space of a human, which, based on Proxemics [L1], includes interactions from physical contact up to approximately 0.5 metres) towards a mutual goal that demands interdependent tasks. Similar to the processes described above for human-human collaboration (HHC), cobots must have the perceptive, cognitive and action capabilities that support joint attention, action observation, shared task representations and spatio-temporal action coordination.

In terms of the sense of agency, the (few) existing studies provide mixed evidence with respect to how this mechanism is manifested during human- (embodied) agent joint action and about the extent to which it follows similar patterns compared to HHC [2]. However, this is a crucial issue in HRC related to the delivery of ethical and trustworthy Artificial Intelligence (AI). Transparency in the authorship of each partner’s actions is related to the ethical dimensions [L2] of: a) human agency, including over- or under-relying on the cobot’s actions, as well as the social interaction instigated; b) accountability, in relation to the ascription of responsibilities if need be; and c) communicating and explaining the decisions of an AI system.

Thus, it becomes clear that HRC must be observed “in action”, that is in real-world and in real-time, in order to not only evaluate the performance of AI methods, but also to study human behaviour towards cobots, and AI agents in general. Luckily, state-of-the-art AI methods now allow us to do so [3]. Towards this, in Roboskel, the robotics activity of SKEL-the AI Lab [L3], we have integrated an HRC testbed [L4] and have initiated a line of studies that aim at exploring team performance using objective measures, as well as subjective human partners’ perceptions of the collaboration. As an example, we briefly describe below our most recent study [L5].

A human and an AI agent had to collaborate and drive the end-effector (EE) of a UR3 cobot, which was moving in a 2D plane, towards a goal position. Each partner was controlling the acceleration of the EE in one axis; the task was quite demanding and involved considerable collaborative learning. The human partner provided desired commands via a keyboard placed on the UR3’s workspace. Seventeen participants were randomly assigned in one of two groups that involved collaboration with one of two different kinds of deep Reinforcement Learning agents: an agent that transferred knowledge (TKa) from an expert team and one that did not. The participants were unaware of the group they were assigned to.

As expected, the collaboration with the TKa significantly affected the time of the collaborative learning and the overall performance; the partners of these teams managed to reach the expert performance within the time provided. Moreover, the overall duration of the training was less than half compared to the other group (33.7 vs 73.1 minutes, respectively). In addition to the objective measures, perceived fluency was also considerably different in the two groups. Surprisingly, it was observed that participants that collaborated with the TKa tended to rate their own contribution and improvement quite high, without acknowledging at the same time the contribution of the robot.

This last result clearly demonstrates the need for further pursuing the research questions described earlier; there is an urgent need for systematically studying and better understanding how people perceive and experience the collaboration with AI (embodied) agents. Just transferring knowledge and results from human-human joint action studies does not seem appropriate; HRC triggers different behaviours. Naturally, this knowledge is necessary for developing ethical and trustworthy AI. On the one hand, AI agents must support fluent collaboration; in this context, some lack of self-agency might be desirable. At the same time, major issues of human agency, transparency and accountability are raised. Real-world studies that shed light on human behaviour during HRC are thus necessary for the alignment of the various ethical dimensions at stake and for adequately advancing the state-of-the-art AI methods.

Links:

[L1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proxmics

[L2] https://altai.insight-centre.org/

[L3] https://www.skel.ai/ , https://www.roboskel.iit.demokritos.gr

[L4] https://ahedd.demokritos.gr/services/human-robot-collaboration-testbed/

[L5] https://github.com/Roboskel-Manipulation/hrc_study_tsitosetal

References:

[1] N. Sebanz, H. Bekkering, G. Knoblich, “Joint action: bodies and minds moving together”, in Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(2), pp.70-76, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2005.12.009

[2] M. Dagioglou, V. Karkaletsis, “The sense of agency during Human-Agent Collaboration”, HRI 2021 Workshop: Robo-Identity: Artificial Identity and Multi-Embodiment, March 8, Virtual, 2021. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1FE_d9E2oR4fW6_9htZMbqpi02ZQbm8cC/view

[3] F. Lygerakis, M. Dagioglou, V. Karkaletsis, “Accelerating Human-Agent Collaborative Reinforcement Learning”, in The 14th PETRA Conference, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1145/3453892.3454004

Please contact:

Maria Dagioglou

National Centre for Scientific Research ‘Demokritos’, Greece