by Gabriele Costa, Francesco la Torre, Fabio Martinelli and Paolo Mori

As a result of the rapid increase in mobile device capabilities, we believe that many users will soon migrate most of their tasks from the computer to the smart phone. We thus feel that new, more effective security mechanisms are needed to protect users, especially minors. For this reason, we are currently engineering a software suite designed to monitor all security-relevant activities and, where necessary, block unsuitable material.

In western countries mobile phones now outnumber people. The majority of these phones have embedded cameras and good connectivity support, connecting to the Internet via their mobile operator network or in wireless mode, and communicating directly with other devices through a Bluetooth interface. This means that the gap in functionality between personal computers and smart phones is being continuously reduced. Mobile devices such as smart phones or Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs) are now powerful enough to run applications that are comparable to those running on normal PCs.

The mobile phone is thus now typically employed for many tasks, such as browsing the Internet, reading and writing e-mails, exchanging data (photos, contacts, files, etc) with other devices, and so on. Clearly, these operations bring with them new vulnerabilities and raise new threats to the user’s privacy. A particular source of concern is the widespread use of mobile devices by young people and minors who can easily access content that is inappropriate for their age. Filters provided by the mobile telco operators are not sufficient to block such material because they only inspect data sent via the telco network and have no control on direct connections (eg Bluetooth). As a consequence, in recent years, much research has focused on the provision of customised, security support for mobile devices. However, what is still missing is a general security framework that controls applications as well as phone calls and message content.

In order to meet this need, by calling upon the experience gained in the EU project S3MS (Security of Software and Services for Mobile Systems), we have developed a new modular security monitor support for mobile devices which uses a plugin-based, extensible architecture to meet the demands of security requirements which change from device to device and from user to user.

Our system aims to monitor all security-relevant activities involving a mobile device. The basic idea is to develop a minimal security core that evaluates the platform security state, accepts customised security policies, and deals with heterogeneous system events.

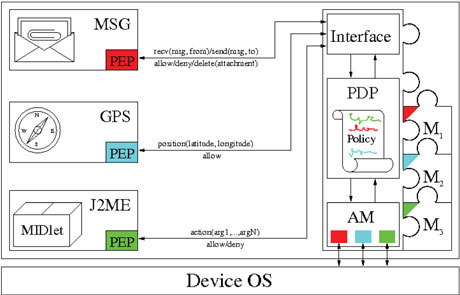

The system can be easily extended with new modules. When, following authentication, a Module M is plugged into the system. It injects the list of its security-relevant events and the new attributes it needs to handle and then disseminates its own Policy Enforcement Points (PEPs) within the device software.

Each PEP checks the behaviour of a critical system component and enforces certain operations (depending on what the PEP is set to monitor). When a PEP captures a sensitive action, it generates a corresponding event and sends it to the system interface. It will then receive the action to be enforced on its target.

Security policies are defined using an editor only accessible by the device owner. The policy editor provides the user with a human-readable graphic interface so that system policy can be defined or modified without the need for technical skills. Security polcies generated by the editor are passed to the PDP to be loaded and enforced.

A very general class of security rules that can involve multiple modules is thus obtained. The example shown in Figure 1 uses three Modules: M1 (red) for messages control, M2 (blue) for position control and M3 (green) for Java applications control. Each module places its own PEP, declares the necessary attributes and specifies their security actions and reactions (labels above and below the connections, respectively). For instance, the PEP watching the transmission of messages sends an action signal whenever a message is sent or received. The action contains information about the message content (msg) and the sender/recipient (from/to). The possible reactions to this event are: allow (if the policy permits the operation), deny (if the policy prohibits it) or delete an attachment (if the message contains dangerous material). Assessment of the danger of an attachment (eg a picture or a video-clip) is done by automatically classifying its content, either remotely on a server or locally on the device itself. The system maps one of its attributes to the classifier invocation and uses it to determine whether a picture is offensive (eg pornographic) or not.

Figure 1: The system core consists of three components: an events interface (Interface), a Policy Decision Point (PDP) and an Attribute Manager (AM). The Interface receives the security events, authenticating and dispatching them to the PDP. The PDP holds the policy defining the currently enforced rules and the security state. Whenever it receives an event from the Interface, it updates the internal state and computes the reaction to be returned. The PDP is able to access some system information through the AM.

Another PEP, attached to the system GPS, gives the geographical position of the device whenever it is available. This information can be exploited to define location-based security policies, eg alerting a parentif the device moves outside certain area.

The last PEP monitors security-relevant operations (eg open/close connections or read/write files) performed by Java MIDlets. This PEP provides valuable feedback on which Java program is executed (method MIDlet.start()).

The large variety of information available to our PDPs makes it possible to apply very expressive constraints. In this way parents can tailor a specific security for their children’s devices. For instance, with a configuration similar to that shown in Figure 1, rules like: "Do not execute Java games at school" or "Alert me with a SMS if the device receives some pornographic content (and block this content)". Such rules can be composed into highly expressive and effective security policies.

Please contact:

Fabio Martinelli

IIT-CNR, Italy

E-mail: