by Tatjana Ćeranić, Stephan Schraml and Philip Taupe (AIT Austrian Institute of Technology GmbH)

Reliable detection of small, local changes in real airborne laser scanning data remains difficult with current 3D change-detection techniques. Off-the-shelf methods often overlook subtle modifications or flag too many false positives. By combining semantics with geometry-based and deep-learning methods, we aim to improve robustness in noisy, cluttered settings.

Airborne laser scanning (ALS) is increasingly used to capture detailed 3D representations of complex outdoor environments. Beyond large-scale urban mapping, ALS enables the monitoring of subtle, localised physical changes, e.g., the sudden appearance or removal of smaller structures or objects – changes that can carry operational or safety implications, particularly in sensitive areas. Detecting these kinds of changes is far more challenging than identifying major modifications such as new buildings or terrain reshaping, yet it is precisely this fine-grained analysis that many real-world applications require.

However, reliably identifying such objects in the highly variable conditions of real ALS acquisitions remains difficult. The changes of interest are typically less than two metres in size, sometimes partially occluded, and recorded under different flight paths. At the same time, the surrounding geometry, such as vegetation, clutter, or naturally irregular surfaces, introduces significant noise and variability. For applications where even a seemingly minor modification can matter, existing 3D change-detection methods do not yet offer the robustness needed in practice.

Why existing methods struggle with real ALS data

Deep-learning methods for 3D change detection are typically trained using publicly available datasets, most of which are synthetic and therefore only approximate real airborne laser-scanning (ALS) conditions. They represent idealised versions of the data: noise-free, uniformly sampled, free of occlusion artefacts, and lacking the complex density fluctuations and natural clutter present in real operational settings. In principle, a dedicated real-world training set could overcome these differences, but assembling one that reflects a specific sensor setup, acquisition procedure, and the range of environmental variability (e.g. seasonal changes) requires substantial effort in data collection and manual annotation. For many applications, creating such a dataset is simply not feasible. Consequently, a domain gap emerges between the synthetic training data and real ALS acquisitions, and models trained on synthetic datasets may generalise less well under real operational conditions, for example by detecting too many false positives.

Classical geometric change-detection techniques (e.g. difference of DEMs, cloud-to-cloud comparison, M3C2) may seem like a robust alternative that does not rely on large amounts of training data, but they also face challenges. In environments with thin or delicate structures (e.g. power lines, flags), dense vegetation, or irregular surfaces, these methods can produce a high number of false detections because they interpret natural variability as structural change.

A hybrid strategy tailored to real conditions

To address these limitations, we developed a hybrid change-detection workflow which combines the strengths of geometry-based analysis with the flexibility of deep learning. Crucially, it functions entirely with a deep-learning model trained on openly available data and requires no additional training data acquisition.

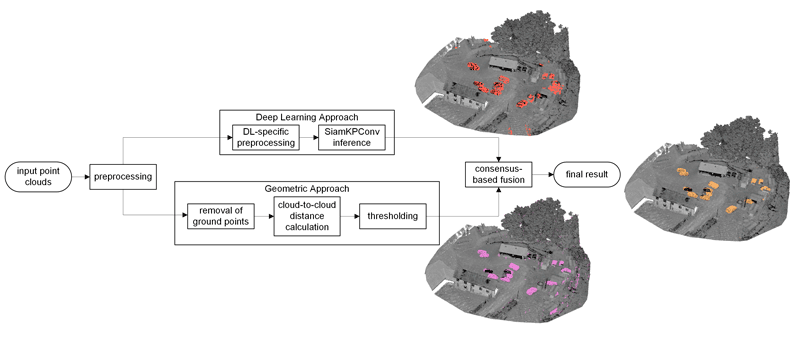

The workflow begins with preprocessing tailored to real ALS conditions. Both point clouds are pre-processed to ensure comparable characteristics (density, denoising, etc.) before the workflow branches into two complementary detection methods:

- A geometric, learning-free change detector: The point clouds are separated into ground and non-ground points using a cloth simulation filter [1]. Only the non-ground points are analysed further, as the focus is on detecting structural or object-level changes rather than terrain fluctuations. Using nearest-neighbour distances between the two surveys, the system flags points that have shifted significantly compared to the reference point cloud. This method excels at picking up clear geometric differences.

- A deep-learning-based detector using a Siamese KPConv network (SiamKPConv) [2,3]:

We use a variant of the SiamKPConv originally developed for urban change detection, trained on the corresponding synthetic dataset. Although the network was trained on a data distribution different from the real-world ALS data, its learned structural features still provide valuable cues for identifying regions likely to represent real physical changes. The SiamKPConv model also outputs semantic labels for detected changes. Although not always fully accurate for ALS data, these labels provide helpful hints about whether a change resembles vegetation, built structures, or mobile objects, thus supporting post-processing filtering and quicker interpretation of unexpected modifications.

Independently, each branch produces its own set of changed point candidates. To reduce false positives, these results are merged using consensus-based fusion: a point flagged by the geometric method must lie close to a corresponding detection from the deep-learning method. This dual confirmation significantly improves reliability in noisy or cluttered scenes, as it ensures that only those changes supported by both geometric evidence and learned features are kept, while retaining the higher resolution provided by the geometric method (see Figure 1; note how the fusion step suppresses vegetation-related noise).

Figure 1: Flowchart of our hybrid change detection approach. Example scene containing changes in the form of vehicles.

What the system can detect

Our current focus is on urban objects such as street furniture, temporary barriers and general clutter. Larger changes, such as new buildings or significant adjustments to existing infrastructure, are also captured reliably. Although detecting vegetation changes is not the system’s primary focus, they are detected to some extent through the deep-learning branch. The semantic labels produced by the SiamKPConv network can further support analysis by suggesting which type of object might have changed.

Outlook

Possible future developments include integrating object-level grouping (e.g. connected components, instance segmentation) to produce map-ready outputs, introducing more advanced semantic descriptors to target specific types of changes. Furthermore, exploring semi-supervised or unsupervised strategies to gradually adapt the deep-learning model to real ALS characteristics could help to bridge the domain gap.

References:

[1] W. Zhang, et al., “An easy-to-use airborne LiDAR data filtering method based on cloth simulation,” Remote Sens., vol. 8, no. 6, Art. no. 501, 2016.

[2] I. de Gélis, S. Lefèvre, and T. Corpetti, “Siamese KPConv: 3D multiple change detection from raw point clouds using deep learning,” ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens., vol. 197, pp. 274–291, 2023.

[3] I. de Gélis, T. Corpetti, and S. Lefèvre, “Change detection needs change information: Improving deep 3-D point cloud change detection,” IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens., vol. 62, pp. 1–10, 2024.

Please contact:

Philip Taupe

AIT Austrian Institute of Technology GmbH, Austria