by Tristan van Leeuwen, Felix Lucka and Ezgi Demircan-Tureyen (CWI)

An image says more than a 1000 thousand words, it is said. This also holds true in many scientific applications, where 2D, 3D, or even 4D images are analysed. But how do we compute images from raw measurements, and can AI help us improve? At CWI’s Computational Imaging group in Amsterdam, mathematicians and computer scientists are trying to answer these questions.

Imaging is a key tool in many sciences. Physicists and material scientists use electron microscopes to study nanoparticles, biologists study organoids under a microscope. At much larger spatial scales, earth scientists use earthquake data to image the deep earth and astrophysicists peer into deep space using telescopes. What unites these fields is that they aim to image things that are not directly observable with the naked eye, or even inaccessible to humans. Advances in instrumentation have revealed things at increasingly smaller scales and at larger distances. Still, direct observation has its limitations – however powerful the instrument – as observations are not always directly related to the features of interest and may contain noise or other imperfections.

To get an interpretable image from the measured data, we need to solve an inverse problem. There, we fit a mathematical model of the image formation process to the measured data. A well-known example is image deblurring, where the imprint of the optical system on the image needs to be removed. A medical CT scan is another well-known example. Here X-ray radiographs are taken from all around the patient and are combined into a 3D reconstruction of the patient’s inner anatomy. In radioastronomy, a similar situation arises and measurements can be processed into a 2D image of part of the sky at a certain distance.

In some cases, when enough measurements of high quality are available, the inverse problem can be solved explicitly and the resulting formulas implemented in software to yield an efficient algorithm that processes the measured data into an image. More advanced mathematical image reconstruction techniques can work with less data and handle more noise, but they require something in return [1]. The missing information needs to be added implicitly or explicitly by making prior assumptions about the object we aim to image. These methods come with two major challenges, however: i) the computational cost of advanced image reconstruction methods is too high for many practical applications; and ii) it is difficult to capture suitable prior information in hand-crafted mathematical models.

So how can AI help us address these challenges? For one, AI can reduce the computational cost of advanced image reconstruction algorithms by replacing an expensive iterative process by a single pass through a deep neural network. The computational cost is then shifted from solving each problem individually to a one-time training phase. This comes in different flavours [2]. Learned inverses treat image reconstruction as pattern recognition, learning to map measurements to images in a single pass. Unrolling integrates physics into the neural network, compressing many iterations into fewer physics-aware steps that reach good solutions faster. Recently, diffusion models have pushed the idea further and allow one to alternate between generating plausible images and fitting the measured data. In our group we are currently working on ways to incorporate physics and measured data into such generative models. Just as you might prompt a text-to-image model, we could then prompt it with “Show me the 3D volume of the chest that could have produced these X-ray radiographs.”

To effectively deploy AI for scientific imaging, though, representative training data are needed. The most impressive AI image generators were trained on billions of images collected from the internet, that are unfortunately not representative for most scientific imaging applications. CWI’s Flex-ray laboratory [L1] is an experimental imaging lab which was founded for the purpose of developing and validating computational imaging algorithms. We use our in-house CT scanner, amongst other things, to collect large datasets specifically for the purpose of testing and validating AI for scientific imaging [3].

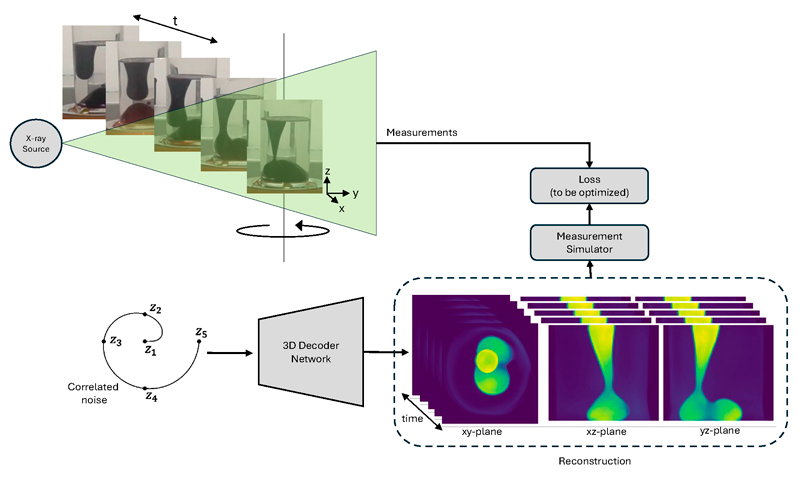

Collecting large data sets comprising measurement data and matching images is difficult and costly, and in medical imaging, further complicated by privacy concerns. In some applications, therefore, we do not have pairs of measurement data and matching ground-truth images. For these cases, we are also actively developing un- or self-supervised training paradigms. In some cases, training data may not be available at all. This happens for example in 4D CT where the object dynamically evolves over time while it is being scanned. A static 3D snapshot of the ground truth needed for supervised training can therefore never be obtained. Surprisingly, neural networks can still help [3]. An example of our recent work is shown in Figure 1, where we use a neural network’s ability to see structure in noise to represent the dynamically evolving image and fit it to the measured data.

Figure 1: Dynamic CT imaging: the object (in this case, a lava lamp) changes continuously, but we can measure only one X-ray radiograph per time frame. To reconstruct the 4D image, we use a neural network’s ability to see structure in noise to represent the dynamically evolving image and fit it to the measured data.

In summary, AI can strengthen computational imaging in several ways. It can be used to speed up the image reconstruction process, promising near real-time performance for specific tasks. Moreover, generative models can capture structure in images in an unprecedented way. It is important, however, that the use of AI in science stays grounded in mathematics and is aware of the underlying physics. The motto should be: model what we can and learn what we must.

Link:

[L1] https://www.cwi.nl/en/collaboration/labs/flex-ray-lab/

References:

[1] S. Ravishankar, J. C. Ye, and J. A. Fessler, “Image reconstruction: From sparsity to data-adaptive methods and machine learning,” Proc. IEEE, vol. 108, no. 1, pp. 86–109, Jan. 2020.

[2] S. Arridge, P. Maass, O. Öktem, and C. B. Schönlieb, “Solving inverse problems using data-driven models,” Acta Numerica, vol. 28, pp. 1–174, 2019.

[3] M. B. Kiss, et al., “2DeteCT—A large 2D expandable, trainable, experimental computed tomography dataset for machine learning,” Sci. Data, vol. 10, no. 1, Art. no. 576, 2023.

Please contact:

Tristan van Leeuwen, CWI, The Netherlands