by Niall M. McMahon, Martin Crane and Heather J. Ruskin

Recent and continuing work in Dublin City University aims to demonstrate the utility

of mathematical and numerical methods for pharmaceutics.

Controlled drug delivery is important for many illnesses. It is often important to ensure that a fixed concentration of drug is available throughout administration of the drug. One type of drug delivery system is the typical tablet that delivers drug as its surface dissolves. Dissolution testing of drug delivery systems is critically important in pharmaceutics. There are three reasons for carrying out dissolution tests: (i) to ensure manufacturing consistency, (ii) to understand factors that affect how the drug enters the blood stream and (iii) to model drug performance in the body. One industry aim is to reduce uncertainty during the development of a new drug. Mathematical and computational simulation will help to achieve this.

Work in Trinity College Dublin, and elsewhere, identified three examples of dissolution physics that are not captured by the well-known Higuchi model. These are: (1) pH changes close to the surface of the dissolving tablet, (2) the effect of particle sizes and (3) the complex hydrodynamics found in typical test devices. The effect of particle size is interesting; large particles of fast-dissolving non-drug additives increase the drug dissolution rate. Understanding how dissolution properties affect drug delivery rates during dissolution seemed a good place for theoreticians to start.

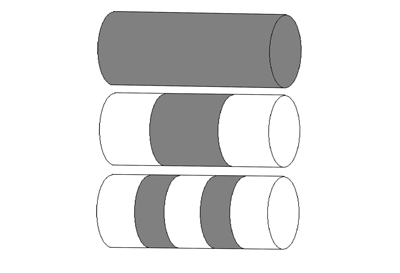

The 1998 Parallel Simulation of Drug Dissolution (PSUDO) project in the Centre for High-Performance Computing at Trinity College Dublin was formed to make improved dissolution models. The team modelled simple cylindrical compacts dissolving in a typical test apparatus. The tablets contained equally-spaced, alternating layers of drug and inert material. This configuration was used because it was a simple starting point and techniques used to model this system might be applied to more complex designs. Finite element code also existed to model dissolution from a layered surface.

Figure 1: 1-, 3- and 5-layer cylindrical tablets. Dark coloured layers consist of drug. Light coloured layers consist of inert materials.

The useful results from the PSUDO project prompted: (i) continued experimental work, in Trinity College Dublin, (ii) efforts to understand the hydrodynamics of typical test devices, again mostly in Trinity College Dublin, and (iii) improvements to the analytical and numerical models of mass transfer; this work was led by our team in Dublin City University. In addition to the authors of this article, the team included Dr. Ana Barat who investigated the use of probabilistic, Monte Carlo based simulation.

Current work

Recent work by the Centre for Scientific Computing & Complex Systems Modelling (Sci-Sym) at Dublin City University has sought to improve on the PSUDO models of dissolution from multi-layer tablets in pharmaceutical test devices; this work applies to the initial and final phases of a dissolving tablet's life. Results from numerical finite difference models were used to assess how changing the surface boundary conditions, in particular, affects the estimate for drug release in the initial stages of dissolution. Experimental data from our colleagues in the School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences in Trinity College Dublin was used to benchmark our results. How one particular surface boundary condition is implemented can lead to relative errors in the calculated drug dissolution rate of about 10% and consequently, is important. However, our work suggests that much of the physics is captured by the current models.

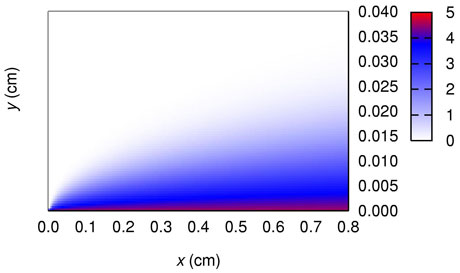

Figure 2: Drug concentration close to the surface of a 1-layer tablet calculated using finite differences. The surface of the tablet is at the bottom of the image and the solvent is flowing from left to right. The concentration scale runs from 0 (no drug present) to 5 (saturated concentration of drug).

The second part of our work looked at dissolution from small spherical particles of drug moving about in the test apparatus; this relates to one possible end-state of tablet dissolution, ie fragmentation. This work involved inserting particles into a flow field, again provided by our colleagues in Trinity, and estimating the dissolution rate, due mostly to convection. One finding was that for particles of diameter 100 microns and smaller, radial diffusion dominates as a mass transfer mechanism. This may help simplify future models.

Most of our work was implemented using Python scripts; we used Crank-Nicolson finite difference schemes, second order accurate in space, first order in the time-like sense. The velocity field within the test apparatus was produced by D'Arcy et al using the commercial CFD code Fluent. LPA and Verlet integration schemes were used to calculate the motion of a particle through the USP velocity field. Mass transfer rates were calculated using empirical correlations.

Future work

In the near future, computing capability, industry needs and a growing acceptance of the utility of cross-disciplinary interaction by professions with strong traditions of experiment, eg, pharmacists, will see the rapid expansion in the use of simulation in pharmaceutical research and development. At present half of the top 40 pharmas use computer simulation. By 2015 it is expected that computer simulation will be a core pharmaceutical research tool.

These two studies, ie (1) drug dissolution from a multi-layered tablet in a dissolution test apparatus and (2) the mass transfer from small particles moving in the test apparatus, each form a part of a future complete framework for simulating drug dissolution in a test apparatus. Work is being continued in DCU by Ms. Marija Bezbradica, a PhD candidate funded by an IRCSET Enterprise Partnership Scholarship.

Acknowledgements

The National Institute for Cellular Biotechnology (NICB) supported much of this research. In addition, the authors acknowledge the additional support of Dublin City University and the Institute for Numerical Computation and Analysis (INCA). Professor Lawrence Crane of INCA was deeply involved in this work as an advisor. Dr. Anne-Marie Healy and Dr. Deirdre D'Arcy et al. of the School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at Trinity College, Dublin, worked with us and allowed us to access and use their computed flow-fields.

Links:

Centre for Scientific Computing & Complex Systems Modelling, Dublin City University: http://www.sci-sym.dcu.ie/

School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Trinity College Dublin: http://www.pharmacy.tcd.ie/

Institute for Numerical Computation and Analysis (INCA): http://www.incaireland.org/

Please contact:

Niall McMahon,

Dublin City University and INCA - Institute for Numerical Computation and Analysis, Ireland.

E-mail:

Martin Crane,

Dublin City University, Ireland.

E-mail:

Heather Ruskin,

Dublin City University

E-mail: