by Jonas Wäfler and Poul E. Heegaard

The increased use of information and communication technology in the future power grid can reduce the most frequent types of failure and minimize their impacts. However, the added complexity and tight integration of an automated power grid brings with it new failure sources and increased mutual dependencies between the systems, opening the possibility for more catastrophic failures.

The power grid plays a crucial role in modern society; the whole economy relies on a dependable power supply. In order to provide this, modern power grids rely heavily on information and communication technology (ICT) for monitoring and controlling. In the next few years, even more ICT devices and systems will be deployed in the power grid, making the system smarter and creating the ‘smart grid’ [1], which will allow a more precise monitoring of the system state and a finer granularity of control.

New systems and services like preventive failure detection and automated failure mitigation come with the aim to utilize the power grid more efficiently and increase the overall reliability. In theory, the automation of processes can reduce the frequency of failures and their severity. When implementing automation of power grids, the primary focus is usually on the most frequent types of failures; those that occur daily, weekly and monthly. A beneficial side effect of automation is a reduction of human effort needed in normal operation.

However, automation brings with it its own challenges. First, the new systems contain more sophisticated software and more configuration possibilities. This makes development, configuration, operation and maintenance more complex and error-prone [2]. Second, the power grid and its supporting ICT systems have mutual dependencies: the ICT systems depend on power supply and the power grid depends on information channels and systems for monitoring and controlling. Such systems are both more complex to analyze and manifest different failure patterns [3]. These failures may not happen in every day operation; they have a low frequency but potentially very serious consequences.

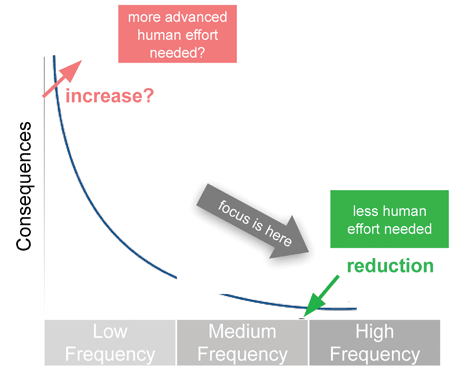

Figure 1: Risk Curve showing how the introduction of ICT may change the consequences of incidents, depending on their frequencies.

Figure 1 depicts the risk curve of a specific system, showing the consequences for incidents with different frequencies. Generally, a high frequency incident has low consequences, but a low frequency (rare) event may have catastrophic consequences. The introduction of ICT focusses on reducing the consequences for high frequency incidents, as shown on the right side of the figure. Automation reduces human effort for these incidents because of a reduction in the number of incidents, and possibly also because of automatic restoration processes. However, there is also a change on the other end of the plot. In the absence of preventative measures, automation can lead to larger consequences in low frequency incidents.

The introduction of ICT focusses on reducing the consequences for high frequency incidents, as shown on the right side of the figure. Automation reduces human effort for these incidents because of a reduction in the number of incidents, and possibly also because of automatic restoration processes. However, there is also a change on the other end of the plot. In the absence of preventative measures, automation can lead to larger consequences in low frequency incidents.

This can be illustrated through an example of the restoration process after a power grid failure. More monitoring and controlling devices allow a fast automatic detection and isolation of a failure. The devices also send diagnostics about the precise failure reason and location, which dramatically accelerates the restoration process. Automation reduces the human effort needed to monitor the system. It reduces the required skill set for the repair crews since the system gives more detailed information about its failure. Additionally, it might also reduce the number of repair crews, as the restoration times are shorter, and owing to better monitoring, a proactive maintenance scheme reduces the number of failures.

However, if the monitoring system fails, the restoration process has to be handled manually again. With a reduced and less skilled repair crew, the consequences of the same outage are bigger. And even more importantly, programming, configuration and operational failures, which are dominant in ICT systems, add additional failures and may lead to very unpredictable states of the system and are more difficult to locate and restore.

In summary, the introduction of automation may have unwanted effects for low frequency incidents. This can be circumvented by the following endeavors: first, by using the saved human effort in normal operation to cover less frequent incidents; second, by increasing the skill set for operational staff to cover new failures and rare events; third, by keeping the staff trained to a high standard and having efficient and well-established processes to deal with rare events.

References:

[1] International Energy Agency (IEA), “Technology roadmap: Smart grids,” http://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/smartgrids_roadmap.pdf, 2011.

[2] P.Cholda et al.,“Towards risk-aware communications networking,” Rel. Eng. & Sys. Safety, vol. 109, pp. 160–174, January 2013.

[3] S. Rinaldi et al., “Identifying, understanding, and analyzing critical infrastructure interdependencies,” IEEE Control Systems, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 11–25, Dec. 2001.

Please contact:

Jonas Wäfler, Poul E. Heegaard

NTNU, Norway

E-mail: